Direct Appeal

What is a Direct Appeal?

The Issues

A direct appeal gives you the opportunity to point out all of the errors made in your case at the District Court level.

The errors that you bring to the appeals court’s attention could be errors at any stage in the process:

Before Trial: An incorrect denial of a motion to suppress, or improper rulings on the admissibility of evidence.

Plea Negotiations: The judge improperly interfering with plea negotiations.

During Trial: The failure of the government to prove its criminal case against you, improper or prejudicial arguments by the government, the District Court’s failure to grant a motion for a judgment of acquittal or motion for new trial, improper rulings on trial evidence as it arises.

Sentencing: Improper statutory or guideline sentencing enhancements, including but not limited to career offender enhancements, 851 enhancements, armed career criminal act enhancements, etc.

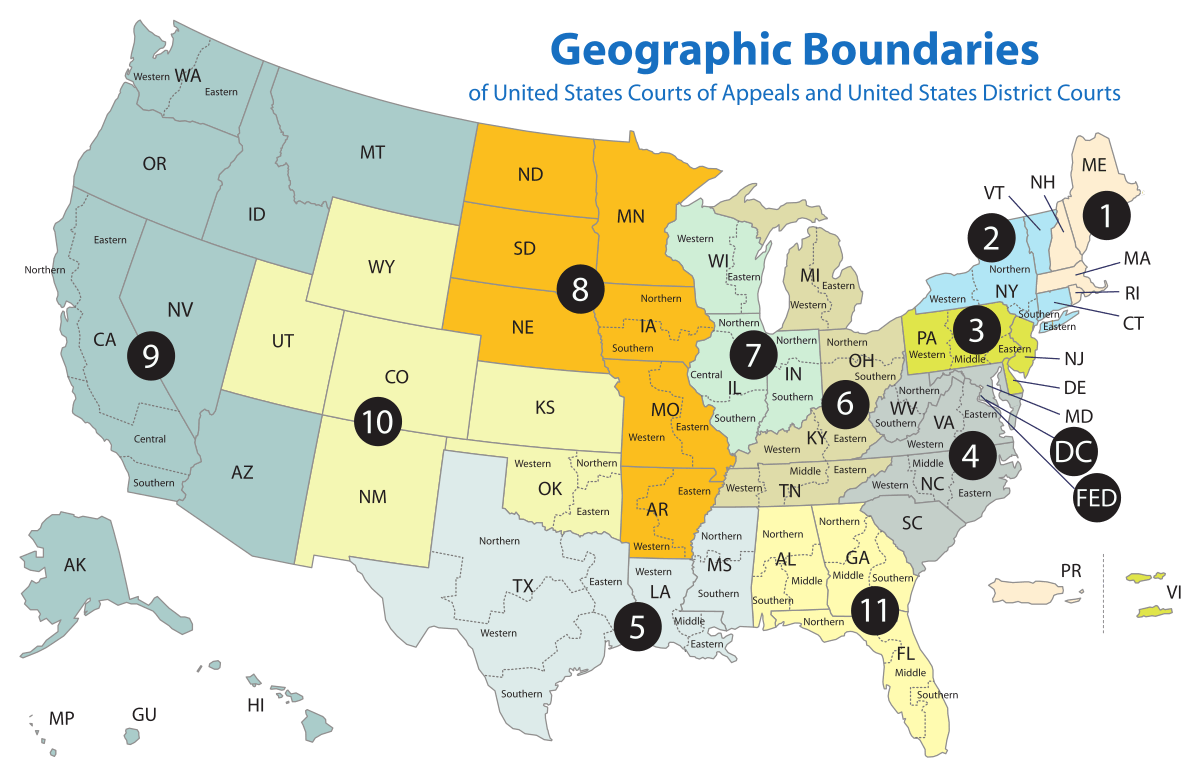

Federal Appellate Courts & Districts

The Direct Appeal Process

Getting Started - The Notice of Appeal

The direct appeal process starts when you file a Notice of Appeal in the District Court where you were convicted. The Notice of Appeal is a simple form, only two pages long. It allows you to give some basic information about your case. Additionally, you will briefly summarize the errors that occurred before the District Court.

Note: You have a very short time within which to file your Notice of Appeal. So, if you believe that an error occurred in your case, you should file the Notice of Appeal as quickly as possible. If you fail to file a Notice of Appeal on time, you jeopardize your chances of appealing your case at all. Federal Law provides that, in a criminal case, a defendant must file a Notice of Appeal in the District Court within 14 days after the:

- Court enters the written judgment;

- Government files a notice of appeal.

Whichever occurs later constitutes the benchmark.

Moving Forward - Federal Appeal Procedure

Once the District Court and Court of Appeals receive your Notice, they assign your case a docket number. You should include it on any future correspondence. You may also receive some preliminary forms to complete.

Secondly, you will receive a briefing schedule from the Clerk of the Appeals Court. It will provide the dates on which you need to file your legal brief.

Thirdly, both you and the government will file appeal briefs in the case. Also, you will also have the opportunity to file a reply brief in response to the government’s appeal brief if you initiated the appeal. This constitutes the most complicated part of the direct appeal process. Accordingly, we highly recommend hiring an attorney to assist. You may request permission to make oral arguments. However, the Court of Appeals ultimately decides whether to have oral arguments.

After considering the briefs, the Court of Appeals will enter a final judgment.

Next Steps

If you win your direct appeal, the court will outline the next steps for your case. Typically, the Appellate Court will tell the District Court precisely what to do. These might include releasing you from prison, holding a re-trial, or holding a re-sentencing.

Petitions for Rehearing and Rehearing en banc

If the court denies your appeal, then you may file a Petition for Rehearing or a Petition for Rehearing en banc before the same Court of Appeals.

A petition for panel rehearing is appropriate when “[a person appealing] believes the court has overlooked or misapprehended” a point of law or fact.

A petition for rehearing en banc (where all the judges from that appellate circuit) is appropriate when:

- An appellate court decision conflicts with a Supreme Court decision or a prior decision from the same appellate court,

- Or the appellate decision involves a question of “exceptional importance.” An example of this would be if the decision conflicts with other appellate court circuit decisions on the same issue.

United States Supreme Court Petitions

Alternatively, you can ask the United States Supreme Court to hear your case by filing a Petition for Writ of Certiorari. If the Supreme Court agrees to hear your case, the appeal process before the Supreme Court largely mirrors the process discussed above. The court will order the parties to submit briefs, and then the court may have oral arguments.

Not every case that is sent to the Supreme Court is heard. The number of cases that the Supreme Court agrees to hear is very few. The types of cases that the Supreme Court hears (as relevant here) are:

- Cases that involve conflicting decisions of how the law should work between circuit courts.

- If the highest court in a given state decides how the law should work in a manner differently than an appellate court decides the same issue.

- If an appellate court decides an “important question of federal law” that should be decided by the court.

- If an appellate court decides something in a way that conflicts with relevant decisions of the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court’s rules indicate that they rarely grant certiorari when the claim is “erroneous factual findings (the court said it happened this way but really it happened this other way)” or “the misapplication of a properly stated rule of law.”

These things can be very tricky and intensive so it is best to reach out to a lawyer in order to determine the right way forward

Frequently Asked Questions

What rules determine whether my direct appeal case is granted or denied?

All litigants before the Court of Appeal must abide by the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure. Those Rules dictate how a direct appeal is handled before the court in extreme detail. As such, an attorney would benefit you greatly in this area.

Additionally, there are different “standards of review” that an appellate court might use. Those standards of review include:

De novo review: the appellate court will use the lower court’s record but will rule on the legal issues without any deference to the lower court.

Abuse of discretion: This may be found when a lower court makes a decision based on “a clearly erroneous finding of fact, rules in an irrational manner or makes a clear error.” Compassionate release cases are an example of a motion that uses this standard on appellate review.

Clear error: “a finding is ‘clearly erroneous’ when although there is evidence to support it, the reviewing court on the entire evidence is left with the definite and firm conviction that a mistake has been committed.” This usually applies to situations where a judge makes a “finding of fact”, such as an evidentiary hearing in a 2255 case. (ex: the parties disagree on whether a lawyer made a promise to a client on how much time they would get. The district court decides that the incarcerated person is more credible. On appeal, the appellate court would use the “clear error” standard to determine the appeal).

Plain error: Used when a person brings up an issue on appeal that was not brought up in the District Court. The Supreme Court has promulgated a four-prong test for Plain Error:

- First, there must be an error or “deviation from a legal rule” that has not been affirmatively waived by the appellant.

- Second, the error must be “plain,” “clear,” or “obvious,” such that it cannot be reasonably contested.

- Third, the error must have affected the appellants substantive rights, meaning that it must be shown that it was prejudicial or affected the outcome of the lower court’s proceedings. The defendant has the burden of persuasion to show such prejudice.

- Lastly, if the first three prongs are satisfied, then the appellate court has the discretion of correcting the error only if the error seriously affects the fairness, integrity, or public reputation of judicial proceedings.

My lawyer filed an "Anders Brief" on my case. What does this mean?

A court-appointed defense lawyer can file an “Anders Brief,” when that counsel wants to withdraw from a case on appeal. Usually, this occurs because he or she believes that the appeal is frivolous. (The term “Anders Brief” comes from a 1967 Supreme Court case on the subject, titled Anders v. California, 386 U.S. 738 (1967)).

In an Anders Brief, a defense attorney must identify anything in the record that might support a direct appeal issue. Once the attorney files the Anders Brief, the Court of Appeals will determine the frivolousness of the appeal. If you have court-appointed attorney who files an Anders Brief in your case, you might want to have a conversation with that attorney about his or her reasons for doing so.

If your attorney filed an Anders brief on your case, you may not have much time to continue to press your appellate rights forward. Please reach out to our office so that we can determine the best way to assist you.

Can I claim ineffective assistance of counsel on my direct appeal?

Yes, but this is VERY RARE. The ineffective assistance of counsel has to be apparent from the record for relief. No new information such as affidavits are allowed. Typically ineffective assistance of counsel claims are brought through a 2255 motion to vacate sentence.

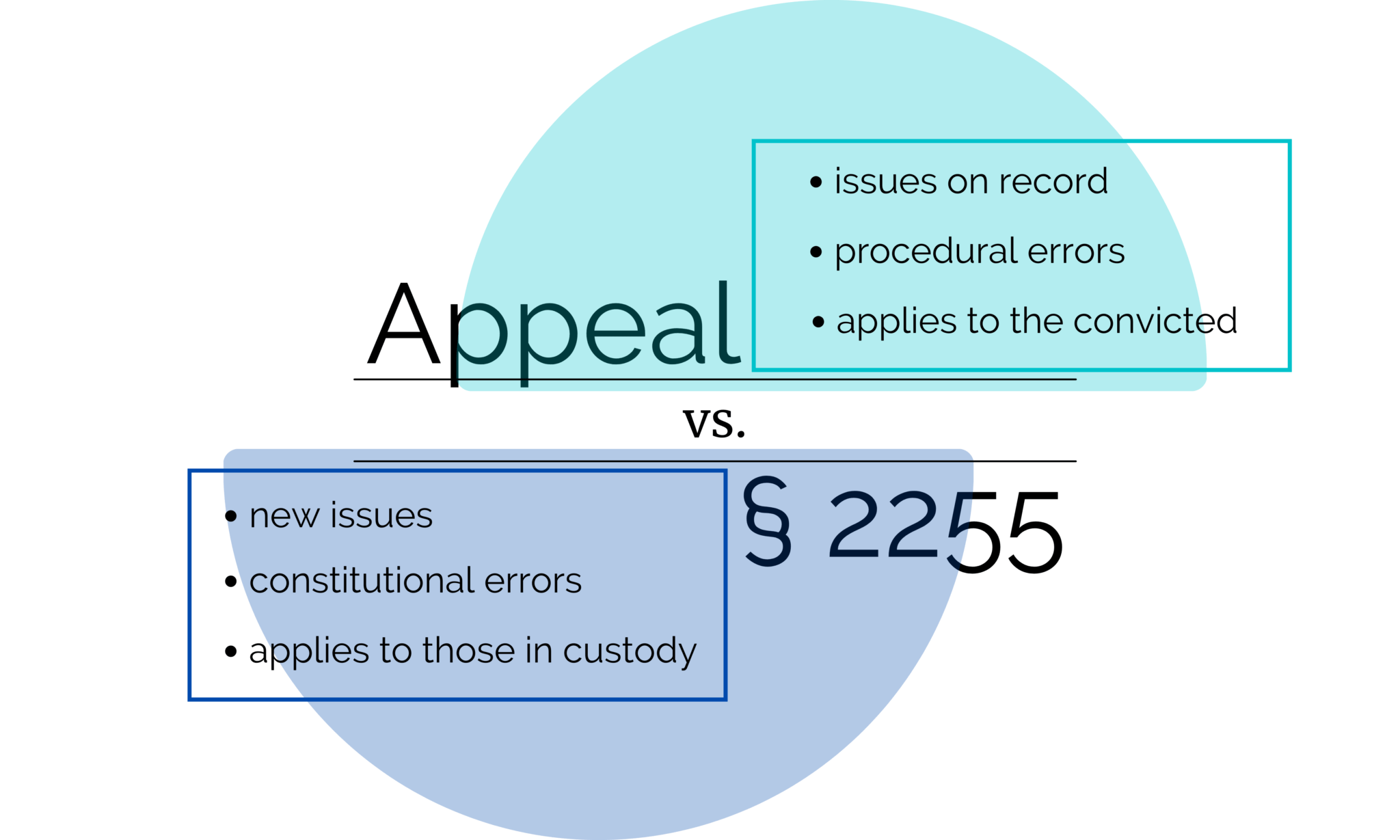

What is the difference between a direct appeal and a 2255 motion?

Can I let the court know if new law comes out after the brief-writing finishes?

Yes. If the law changes in a way that impacts your case after all the briefs in your case have been filed, then you can alert the court to that change while your direct appeal is pending. This is colloquially called a “28(j) letter.”

My attorney says that I signed an appeal waiver in my plea agreement. What does this mean?

Typically part of a plea agreement, an “Appeal Waiver” states that you agree to forego, or “waive,” your right to make a direct appeal your case. If you pleaded guilty and accepted a plea agreement, you likely signed an Appeal Waiver.

With Appeal Waiver, you cannot file an appeal, except in certain circumstances. For example, if the sentencing court grants an upward departure from the sentencing guidelines, you may have the ability to appeal that decision. However, the Appeal Waiver you signed must be specific about what post-conviction remedies you waived. If there is no mention of possible appeal remedy in the plea agreement, then courts will likely find that that particular remedy was not waived.

In short, having signed a Waiver may limit the kinds of relief you can request on appeal. But, it does not necessarily foreclose all avenues of appeal. A qualified Federal Appeals Lawyer can help you better understand what options you have available to you if you did sign such a Waiver.